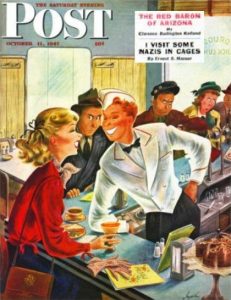

Op pagina 101 van het poëtisch celdagboek kleefde Nand enkele fragmenten uit het Amerikaanse magazine “The Saturday Evening Post” van 11 oktober 1947. Het wekelijks magazine kent een rijke geschiedenis, het verscheen voor het eerst in 1821 en was erg populair. Het werd in 1969 opgedoekt, maar verscheen in 1971 opnieuw en bestaat nog steeds.

De bladzijde waarop de fragmenten gekleefd zijn is niet gedateerd, maar enkele bladzijden vroeger, op pagina 96, staat wel een datering: 13/12/48. Op dat ogenblik bevond Nand zich in het interneringscentrum te Merksplas, de laatste gevangenis waar hij verbleef. Hij was daar aangesteld als medewerker voor de “Welfare”, in zijn woorden: “Hier was ik Vlaamse animator die voor ontspanning zorgde, teksten voor liederen schreef, scenario’s van shows opstelde en zelf ook nog de affiches schilderde.” In die functie had hij waarschijnlijk toegang tot de bibliotheek met beschikbare tijdschriften, ook degene die meegeleverd werden in het kielzog van de Amerikaanse troepen.

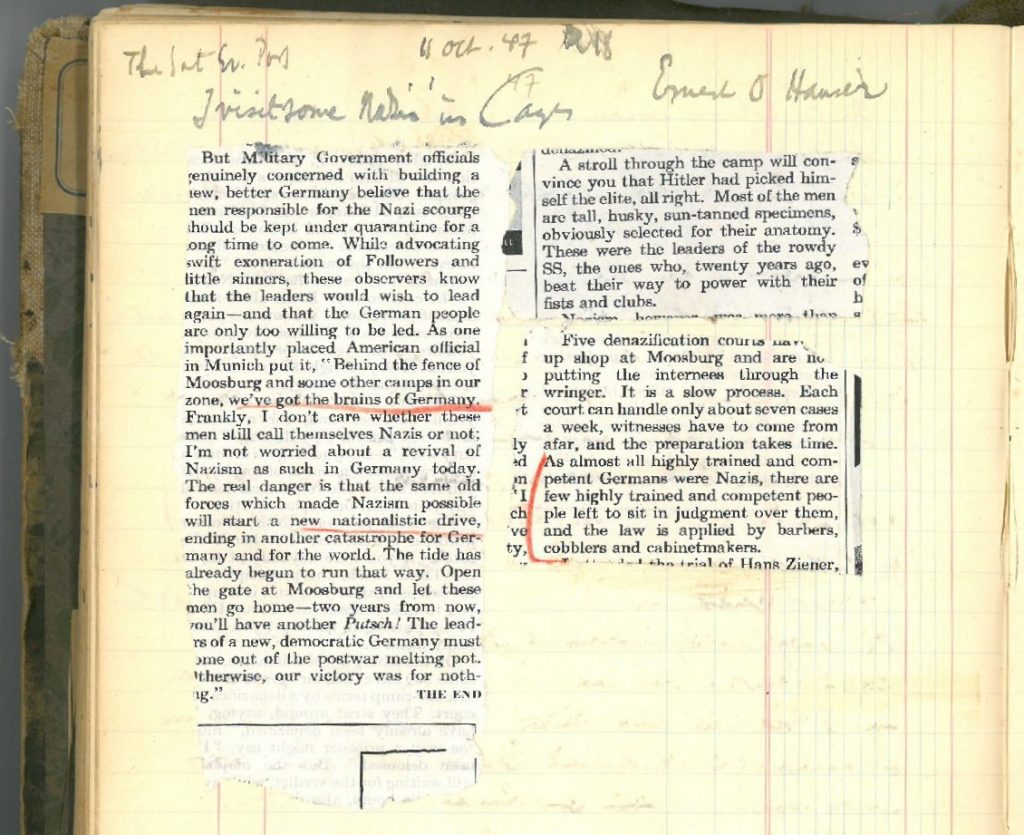

De ingekleefde fragmenten:

Deze fragmenten geven een indicatie over hoe Nand over de historische feiten dacht.

Bovenaan in potlood de bron:

The Sat Ev; Post 11 oct. 47 p.18

I visit some Nazis in Cages Ernest O Hauser

(rode aangekruiste passages hieronder onderstreept)

“But Military Government officials genuinely concerned with building a new, better Germany believe that the men responsible for the Nazi scourge should be kept under quarantine for a long time to come. While advocating swift exoneration of Followers and little sinners, these observers know that the leaders would wish to lead again – and that the German people are only too willing to be led. As one importantly placed American official in Munich put it: “Behind the fence of Moosburg and some other camps in our zone, we’ve got the brains of Germany. Frankly, I don’t care whether these men still call themselves Nazis or not; I’m not worried about a revival of Nazism as such in Germany today. The real danger is that the same old forces which made Nazism possible will start a new nationalistic drive, ending in another catastrophe for Germany and for the world. The tide has already begun to run that way. Open the gate at Moosburg and let these men go home – two years from now, you’ll have another Putsch! The leaders of a new, democratic Germany must come out of the postwar melting pot. Otherwise, our victory was for nothing”.

THE END

A stroll through the camp will convince you that Hitler had picked himself the elite, all right. Most of the men are tall, husky, sun-tanned specimens, obviously selected for their anatomy. These were the leaders of the rowdy SS, the ones who, twenty years ago, beat their way to power with their fists and clubs.

Five denazification courts have set up shop at Moosburg and are now putting the internees through the wringer. It is a slow process. Each court can handle only about seven cases a week, witnesses have to come from afar, and the preparation takes time. As almost all highly trained and competent Germans were Nazis, there are few highly trained and competent people left to sit in judgment over them, and the law is applied by barbers, cobblers and cabinetmakers.”

Online zijn afbeeldingen te vinden van de voorzijde van het tijdschrift:

Inhoudsopgave:

Detail inhoud (links fragment van het eerste artikel, rechts reclame):

Dankzij mijn neef, die in de Verenigde Staten woont, kon ik een origineel exemplaar van het tijdschrift op de kop tikken. Weergave van eerste bladzijde en de bijhorende foto’s. Daaronder de volledige tekst van het artikel.

Eerste bladzijde:

Foto’s en onderschriften:

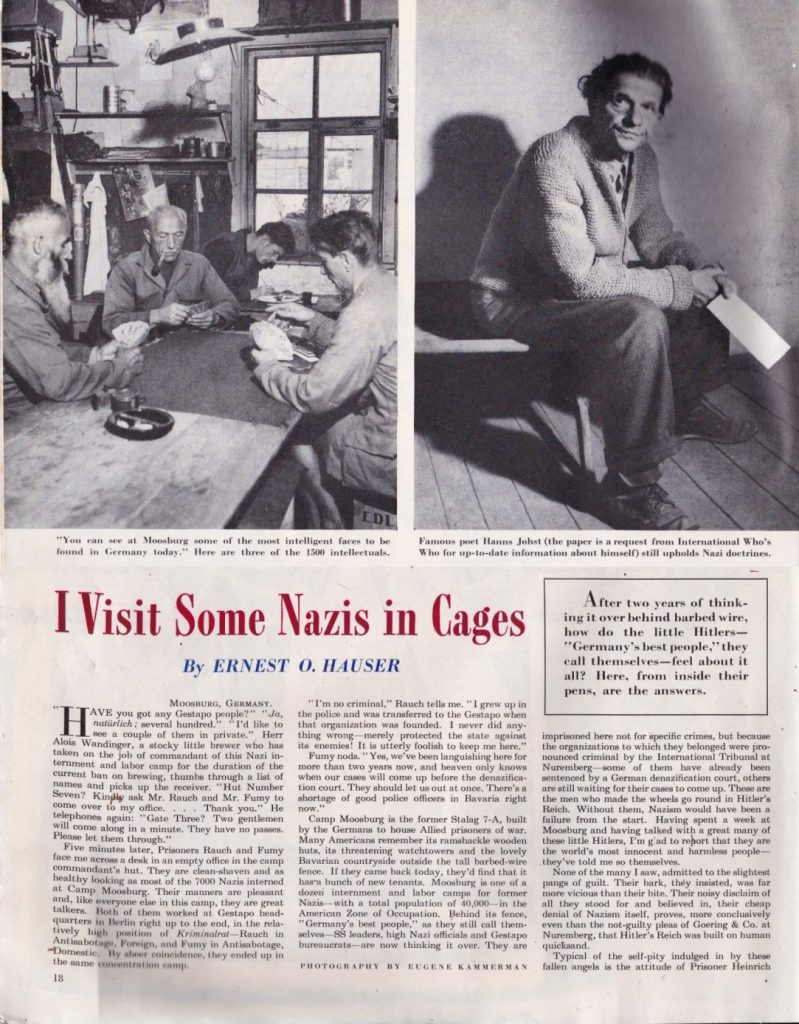

Famous poet Hans Johst (the paper is a request from International Who’s Who for up-to-date information about himself) still upholds Nazi doctrines.

> nvdr: Johst was ook deelnemer aan de “Dichterreis door Duitsland“, hieronder een foto uit het “Reisalbum” tijdens het Dichtertreffen in Weimar, oktober 1941. Links (in uniform) Johst, 3de rij Nand, eerste rij tweede van rechts Goebbels:

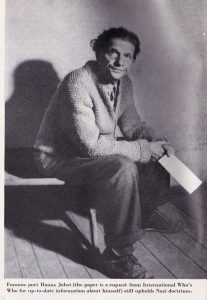

“You can see at Moosburg some of the most intelligent faces to be found in Germany today.” Here are three of the 1500 intellectuals.

Politics is forbidden, but this copy of the Russian Izvestia turned up in the camp.

“They are the world’s most innocent and harmless people – they’ve told me so themselves.” Husky physically and very sharp mentally, fewer than one fourth of the “labour” camp’s inmates do any labor.

(nvdr: de door Nand uitgeknipte passages staan hieronder in cursief)

I VISIT SOME NAZIS IN CAGES

by Ernest O. Hauser

Photography by Eugene Kammerman

“After two years of thinking it over behind barbed wire, how do the little Hitlers – ‘Germany’s best people,’ they call themselves – feel about it all? Here, from inside their pens, are the anwers”

October 11, 1947, Moosburg, Germany.

“Have you got any Gestapo people?” “Ja, natürlich; several hundred.” “I’d like to see a couple of them in private.”

Herr Alois Wandinger, a stocky little brewer who has taken on the job of commandant of this Nazi internment and labor camp for the duration of the current ban on brewing, thumbs through a list of names and picks up the receiver. “Hut Number Seven? Kindly ask Mr. Rauch and Mr. Fumy to come over to my office…. Thank you.” He telephones again: “Gate Three? Two gentlemen will come along in a minute. They have no passes. Please let them through.”

Five minutes later, Prisoners Rauch and Fumy face me across a desk in an empty office in the camp commandant’s hut. They are clean-shaven and as healthy looking as most of the 7000 Nazis interned at Camp Moosburg. Their manners are pleasant and, like everyone else in this camp, they are great talkers. Both of them worked at Gestapo headquarters in Berlin right up to the end, in the relatively high position of Kriminalrat-Rauch in Antisabotage, Foreign, and Fumy in Antisabotage, Domestic. By sheer coincidence, they ended up in the same concentration onmp.

“I’m no criminal,” Rauch tells me. “I grew up in the police and was transferred to the Gestapo when that organization was founded. I never did anything wrong-merely protected the state against its enemies! It is utterly foolish to keep me here.”

Fumy nods.” Yes, we’ve been languishing here for more than two years now, and heaven only knows when our cases will come up before the denazification court. They should let us out at once. There’s a shortage of good police officers in Bavaria right now.”

Camp Moosburg is the former Stalag 7-A, built by the Germans to house Allied prisoners of war. Many Americans remember its ramshackle wooden huts, its threatening watchtowers and the lovely Bavarian countryside outside the tall barbed-wire fence. If they came back today, they’d find that it has a bunch of new tenants. Moosburg is one of a dozen internment and labor camps for former Nazis-with a total population of 40,000—in the American Zone of Occupation. Behind its fence, “Germany’s best people,” as they still call themselves—SS leaders, high Nazi officials and Gestapo bureaucrats-are now thinking it over. They are imprisoned here not for specific crimes, but because the organizations to which they belonged were pronounced criminal by the International Tribunal at Nuremberg-some of them have already been sentenced by a German denazification court, others are still waiting for their cases to come up. These are the men who made the wheels go round in Hitler’s Reich. Without them, Nazism would have been a failure from the start. Having spent a week at Moosburg and having talked with a great many of these little Hitlers, I’m glad to report that they are the world’s most innocent and harmless people they’ve told me so themselves.

None of the many I saw, admitted to the slightest pangs of guilt. Their bark, they insisted, was far more vicious than their bite. Their noisy disclaim of all they stood for and believed in, their cheap denial of Nazism itself, proves, more conclusively even than the not-guilty pleas of Goering & Co. at Nuremberg, that Hitler’s Reich was built on human quicksand.

Typical of the self-pity indulged in by these fallen angels is the attitude of Prisoner Heinrich Hoffmann, Hitler’s side-kick and personal photographer. To my question, “Have you got a minute?” he airily replied, “I’ve got ten years”—referring to the maximum labor-camp sentence which he drew for what might be termed the world’s outstanding retouch job.

We talked at length, and the angry little man, who looks like one of the lesser dwarfs out of Walt Disney’s Snow White, chatted freely about the terrible wrong done to him.

“What makes me particularly mad is that I only joined the Nazi Party, back in 1920, because an American outfit had offered me a thousand dollars for an exclusive picture of Hitler. How could I hope to get it without becoming a Nazi myself? My motives were purely professional!” He ruefully recalled how, when he finally clicked the shutter, Hitler had him beaten up and the film destroyed— “It took us some time to become real friends.” One afternoon several years later, when Hitler dropped in at his Munich photo studio for a cup of tea, Hoffmann introduced the future Führer to his newly hired receptionist, Eva Braun.

“Do you pick them for looks or for talent?” Adolf asked.

“Not every pretty girl is stupid,” said Hoffmann. The photographer smiled wistfully as he remembered those golden days.

“And now I’m being incarcerated with all these small-fry Nazis with whom I never used to associate before!” The compliment, I learned later, was cordially reciprocated; known as the loudest squawker in the camp, “profiteer” Hoffmann enjoys a minimum of popularity among his fellow inmates. In fact, no one here has much love for the bigwigs in the camp. Few of these “little Führers,” important though they were in the Third Reich, ever hobnobbed with members of the inner circle. Seeing their great men at close range for the first time and hearing them tell tales out of school, the rank and file now voice disgust with “those conceited asses who always took us in.”

One man whose backbone is still intact after the great fall is fifty-seven-year-old Hans Johst, renowned Nazi poet and a general (“I wouldn’t take anything less”) in the SS. He entered the party after a dramatic audience with Hitler during which the Führer told him that “he wanted to build his Reich upon arts and literature.” In recognition of the wide appeal of Johst’s writings—among them a play called Tom Paine-Doctor Goebbels appointed him president of the Reich’s Authors’ Guild in 1936. Johst sticks to Nazism even today. Unlike Hoffmann, he proudly identifies himself with the Nazi regime and has nothing but contempt for the spineless butterflies around him. “They claim they had no part in it, the cowards! How can a man erase an entire period of his life? I disagree with many things the Nazis did, but I still say National Socialism is the only system that suits us Germans.”

The tall, unshaven man with burning eyes, who usually wears a coarse woolen sweater and short pants and likes to accompany his speech with wild gestures, is the most colorful figure in this camp. His case has not yet come up before the denazification court, but he isn’t marking time–the poet general is busily working on a new novel.

A lone American, twenty-six-year-old Capt. T. 0. Meyer, of Buffalo, New York, serves as supervisor at Camp Moosburg, staffed entirely by Germans. Sitting in a small shack near the main entrance, he is wondering what would happen if, some fine morning, his 7000 charges should decide they didn’t like his looks. As it is, Meyer, who speaks fluent German and doesn’t mind if a Nazi engages him in a long debate on Germany’s past and future, is probably the most popular person in Moosburg.

As representative of Military Government, Meyer retains the final say in such matters as furlough, complaints and punishment. He’s got his problems. “Take the guards, for example,” he told me. “We have about six hundred of them-mostly no-good bums. You simply can’t find good people to work for a hundred marks (ten dollars) a month if one package of cigarettes costs a hundred marks in the black market. Many of these fellows have come into Bavaria from other parts of Germany and we can’t check on their past careers. They’ve got American carbines and automatics, but who can tell whether they’d ever use them?”

Had any of his prisoners escaped? – “Thirty-two last week,” Meyer grinned. – “What can I do? They just walk out the front door. It costs a fellow from three to five packages of cigarettes to get out of here, and they can get the cigarettes from their friends and families outside. It’s easy. Why don’t all of them pack up and leave? The majority here are in their late forties and don’t care to play hide-and seek with the German police; they want to get back to their families properly denazified.”

A stroll through the camp will convince you that Hitler had picked himself the elite, all right. Most of the men are tall, husky, sun-tanned specimens, obviously selected for their anatomy. These were the leaders of the rowdy SS, the ones who, twenty years ago, beat their way to power with their fists and clubs.

Nazism, however, was more than bloody noses and cracked skulls. Side by side with these SS hulks, you can see at Moosburg some of the most intelligent faces to be found in Germany today. About 1500 of the internees qualify as intellectuals—the brain trusters of the Third Reich. They have studied law, economics, physics and medicine at some of the best universities of Europe, and many of them are leaders in their respective fields. Even now, they insist on being called “Herr Doktor” by their fellow prisoners.

I stumbled into high-grade professionals everywhere. Moosburg prides itself on its hospital, staffed by some of Germany’s outstanding surgeons and specialists.

The camp kitchen is presided over by Dr. Emil Ruppert, a circuit judge and captain in the Waffen SS. “What is guilt?” he asked me. “How do you constitute a cause-and-effect relationship in our cases?”

The tailor shop is run by Wilhelm Jungermann, war correspondent on the Balkan front and sergeant in the SS. “As an intellectual, I have to look at this thing with my intellect-the downfall of Nazism is the mutiny of the spirit after twelve years of frustration.”

Many of these mental giants, asked a simple question, will reply with what amounts to a Ph.D. thesis. It is only fair to say that more ten-dollar words are used in Moosburg than anywhere else in Germany today.

Although this is supposed to be a labor camp, fewer than one fourth of Moosburg’s inhabitants actually labor. Only a few of the lesser sinners are permitted on work details outside the camp-some of them make cheese in the Moosburg dairy, others work at garbage disposal, unload freight cars at the station or are farmed out to a local construction firm. The majority of the working prisoners are employed inside the camp, in the kitchen, tailor shop and motor pool. All of it is purely voluntary. Far from paying its own way, Camp Moosburg costs the Bavarian Government the equivalent of $4,500,000 a year.

The food ration of 1700 calories a day evidently agrees with the inhabitants of the camp, most of whom look healthier than their compatriots outside the barbed-wire fence. As a rule, whatever comes in ends up in a soup, and the standard menu of half a pound of bread for breakfast, and a bowl of soup for lunch and supper does not offer much variety. Those receiving food packages usually share the contents with their less fortunate brethren.

“It is wonderful to see people act with such generosity,” one Nazi marveled. “True socialism at last!”

Compared to the comfort in which these 7000 leading Nazis lived before it was all over, Moosburg is dreary enough. Compared to one of the concentration camps to which they sent their victims, Moosburg is paradise. It all depends on how you look at it. Discipline, for one thing, is lax. The punishment for flagrant disrespect of the rules is two or three days of solitary confinement-fifteen days, thus far, has been the maximum. Within the obvious limits, everyone does pretty much as he pleases. The staff addresses the internees as “Herr,” or “Mister.” Their class prerogatives are fastidiously preserved—I’ve seen prisoners dress down some of the guards on duty in the language of a sergeant telling off a rookie.

The prisoners wear civilian garb and many of them sport wrist watches and gold rings. They are free to receive packages, write and receive letters, and are visited by their relatives once a month for two hours, in addition to visits by their lawyers and other business calls. Furlough is granted in case of death or severe illness in the family.

The huts are comfortable and there’s plenty of room to move around. Each prisoner has a good-sized bunk to himself— nothing like the sardine-tin sleeping shelves at Dachau-and enough space for his belongings. During the winter, the huts are better heated than the average German home. Each group of eight prisoners has a long wooden table, and you can see them sitting around it most of the day-talking, smoking, reading, playing chess. The camp has a fair library, run by Joseph Schweyer, of the Horse SS. Travel and history books, Schweyer told me, are the most popular, next come books on agriculture and engineering. Pocket-sized English-language books of the type especially printed for the United States Army are in great demand.

If the prisoners get tired of reading books or playing chess, they have a fine orchestra, made up of Nazi musicians, and a better-than-average theater, to divert them. Lectures on various subjects are given every night.

In this barbed-wire Eden, where the SS lion lies down with the Gestapo lamb, politics is the forbidden fruit. No one is allowed to propagate the ideas of one of Germany’s new political parties, and few of the prisoners object to this sensible rule. Curiously enough, a “Club for Democracy” has sprung up in the camp without any prodding from outside the fence. It counts about 100 members, among them lawyers, teachers, party functionaries, bakers, plumbers and bricklayers. In a typewritten statement of their aims and ideas, these men claim that they have “completely broken with Nazism and earnestly wish to study every aspect of democracy.”

Shepherded by Dr. Karl Huber, a physician in the Horse SS, the club meets every Wednesday at eight P.M. in Hut No. 1 to discuss such topics as the French Revolution or the Constitution of the United States. So far, these converts have not run into any serious trouble; though now and then, one of their more simple-minded comrades finds their odor of sanctity a bit too much to take. One diehard, after listening to a lecture on the rights of man, dramatically bared his chest, shouting, “I’ve always been a Nazi! I’m still a Nazi! Shoot me, but I won’t budge!”

There also exists, believe it or not, a communist organization known as “Friends of the Soviet Union” in this camp. None of the members, thus far, have been identified, as the group convenes in secret, requesting its members, by notices posted on the walls, to meet at the accustomed place.” Not long ago, communist slogans mysteriously appeared all over the camp “Democracy? Nonsense! Stalin will help us.”

When Mr. Wandinger, the commandant, asked some of his prisoners to remove them, these upright Nazis refused, saying, “Maybe one of our judges will be a communist. Then we’ll be in the soup.”

It may be true, as many of the prisoners insist, that in a free and secret election only about one in every five of them would vote the straight Nazi ticket. It may be true that Nazism was 90 per cent intoxication and that the collapse probably did have a sobering effect. But where to go from there? Lacking even the most elementary concepts of democracy, these 7000 pillars of the Third Reich were completely stumped last June when they were told to elect a spokesman from their midst. In good totalitarian fashion, a clique of strong-armed block leaders simply proposed a candidate, and, of course, there was no opposition. SS Major Herbert Menz, a former actor and radio commentator, was-returned with 5000 votes against 100. Menz is the Hollywood type of the sly and loudmouthed Nazi bully, and many of the prisoners told me in private they did not like the idea of being represented by him in their dealings with the commandant, but what could they do?

The prisoners themselves are beginning to get on one another’s nerves. The 100-odd men who share one of the large rooms, of which there are two to each hut, are not unlike fellow passengers on a ship—the journey has lasted more than two years now, and they’re sick of looking at one another. “I know every line in everyone’s face, and every chapter in everyone’s life story by now,” one of them sighed.

Most of these men are acutely sorry for themselves, and idleness is a poor medicine for self-pity. Their morale is below zero. I listened to several complaints. about us, the best people in Germany, being turned into proletarians in this camp;” and one or two threats of “We’ll be nihilists by the time we graduate.” Many of the prisoners, however, are genuinely worried about their families, which, deprived of the breadwinner, find it difficult to keep their heads above water. “My wife has sold my skis,” one Gestapo man told me, “and my tennis racket went for the last cigarettes she sent me. Her fur coat will go next.” Another prisoner with whom I talked had just received word that his four-month-old son had died of starvation in Berlin.

Most of the prisoners’ talk, of course, revolves around the question: “When do I get out?” It is a tricky subject. Almost all of them are thoroughly familiar with every article of the denazification law under which they are to pay the price for their twelve-year hayride. This remarkable instrument, officially known as “Law for Liberation From National Socialism and Militarism,” was hammered out by American and German minds after the war. It is about as simple as your income-tax form, and could not have been conceived more brilliantly by Alice had she set out to denazify the inhabitants of Wonderland. One enterprising SS sergeant, a graduate of the universities of Munich and Vienna, has set up a legal bureau in the camp and gladly chaperons his comrades through the maze of legal clauses free of charge. So roughly speaking, the denazification law divides all culprits into four groups: Major Offenders; Offenders (Activists, Militarists and Profiteers); Minor Offenders; and Followers. The idea is to exclude the leading culprits forever from the main body of “good Germans” and restore the “little Nazis” to the community. If the all-German denazification court pronounces you a member of one of the first two groups, you are subject to a labor-camp term, you have lost your right to vote, and you are permanently ineligible to hold a public office. If you’re a Minor Offender, you’ll be fined and, for a certain probation period, may do only “ordinary work”—but you’ll again become a fully recognized member of society. If you are a mere Follower, a small fine will buy your immediate rehabilitation. The thing you want to be, in other words, is a Follower. But here’s the catch: If you were anybody at all in the Third Reich, the presumption of the law is against you, and it is up to you to talk yourself into Group III or IV by proving to the court you didn’t really mean it.

Of Moosburg’s 7000 inmates, only some 500 have thus far been sentenced to labor-camp terms by a denazification court. They strut around, saying, “I have already been denazified,” much the way a prisoner might say, “I’ve been deloused.” But the majority, still waiting for the verdict, while away their idle hours, absorbed in speculation on their final fate, and their chitchat will run like this:

“So you think they’ll make you an Activist, Herr Doktor?”

“It depends on the kind of judge I’ll get, Herr Professor. Ach, if it weren’t for that purely honorary rank in the SS, I might wangle a Group Three sentence.”

“Me, I joined the party in 1933, but I have two witnesses to prove that I called Hitler a liar in 1939!”

Even though the black-uniformed SS, to which nearly one half of these prisoners belonged, was a law unto itself in Hitler’s Reich, privileged to kill, there isn’t an SS man at Moosburg today who cannot “”prove” that he, personally, was a Weisser Rabe-a white raven. All these men, who for twelve years lorded it over the German nation, now collect alibis with the same childlike perseverance with which your son collects stamps.

“We’d love to forget our past,” one angelic Gestapo man told me, “but in order to prepare our cases, we have to sit and ruminate all day long, trying to remember every mitigating circumstance.”

The prize alibi, of course, is a Jew. In hearing the prisoners talk about the kindly interest they always took in their Jewish compatriots, one might easily think that the Nazi Party was a society for the care and protection of Judaism. “I was working at Gestapo headquarters one morning,” another Nazi told me, “when they were interrogating a Jewish gentleman, and I heard them whisper they’d arrest him after lunch. So, when they told him he could go out for a sandwich, I took him aside and said, ‘If I were you, mister, I wouldn’t come back.’ I’m sure that gentleman would gladly testify on my behalf, but heaven knows where he’s gone.”

When a man’s day in court finally arrives, he shaves carefully, gets himself a haircut, puts on a clean shirt and walks over to the special enclosure where justice is dispensed. The courthouse is a simple barnlike hut of the same type that houses the internees. There is no fanfare. As this is an all German affair, no Americans are present. There are no emblems of Sovereignty, either—no eagles, no flags. The three judges, seated behind a table covered with a faded rug, wear threadbare business suits. Everything is informal. Just the same, the nerves of the accused are tauter than a tightrope.

Five denazification courts have set up shop at Moosburg and are now putting the internees through the wringer. It is a slow process. Each court can handle only about seven cases a week, witnesses have to come from afar, and the preparation takes time. As almost all highly trained and competent Germans were Nazis, there are few highly trained and competent people left to sit in judgment over them, and the law is applied by barbers, cobblers and cabinetmakers.”

I attended the trial of Hans Ziener, local party leader—Ortsgruppenleiter of a working-class district in the city of Nuremberg. There was no one to testify against him, as it is getting to be dangerous for a German to turn state’s witness against a Nazi these days. Ziener’s defense, on the other hand, was elaborate. Of his four witnesses, one was a communist who had spent twelve years in a concentration camp and who gave the accused a clean bill of health. But the main point of Ziener’s plea was that, in the spring of 1945, when it was his duty to rally the Volksturm for a last-ditch defense, he had sent those good people home—thus enabling our “American liberators” to enter Nuremberg from his side of town without meeting resistance.

The prosecutor, a member of the Communist Party, addressed the court with the lifeless voice of a man who is tired of talking to a stone wall, “Who solidified Nazi power? Who maintained constant pressure upon the people? Men like this. Without a Ziener in every town, Nazism wouldn’t have lasted a day. But if Hitler himself were brought before this court, he’d have a thousand witnesses telling you gentlemen what a grand fellow he was. And you would probably acquit him.” He considered Ziener an Activist, and asked for a stiff labor-camp term. The sentence: Group III–Minor

Offender. Ziener was released on probation and fined 4000 marks $400). He walked out of the courtroom grinning like a monkey.

The over-all picture emerging from this and many similar trials is not pretty. The denazification machine, handed over by the conquerors to the conquered in March, 1946, is completely bogged down now. German apathy, fear and, in many cases, downright sabotage have turned the epuration process into a farce. The Germans, never given to revolutionary action, simply didn’t take to this “revolution by law” with which the victors tried to saddle them. Thousands of cases, appealed by the accused or by the prosecutor after the lower court has spoken, are dragged endlessly through the higher courts and often kicked back and forth indefinitely. Throughout our zone, 1,000,000 Nazis are still waiting trial, and at this rate it will take another five years before the last of them knows just where he stands.

Bavaria, where Nazism was born, remains the crux of the problem. In this southern state which has the largest number of Nazis in the American zone, only 18 per cent of those considered Major Offenders and Offenders-Groups I and II—have thus far been tried. And of the 2046 actually charged as Major Offenders—Group I only 315 have been placed in that top guilty class by the courts, while the rest got away with milder classifications. The German grocers and brewers now judging their former lords do not want blood. In an effort to stem the tide of leniency, Military Government is now bringing pressure to bear on the Bavarian Government to have as many cases as possible vacated and sent back to the bench for retrial, thus further retarding the slow motion.

Meanwhile, the fallen heroes at Moosburg twiddle their thumbs, wondering whether they’ll go to hell or Valhalla. And while they are twiddling, the question may well be asked: Why not forget the whole unpleasantness and let these sulky supermen go home? Most Germans, no doubt, would welcome such a solution. So, for that matter, would some Americans who are rubbed the wrong way by seeing these men imprisoned for their opinions and punished for the jobs they held, rather than for specific crimes.

Besides, the brain trusters behind the fence-opportunists from way back-are now beginning to present themselves as Germany’s only hope against communism. “The Bolsheviks are coming,” some of the men at Moosburg told me, “and we are the only ones who can stop them.” Their persistent cries of, “Let us out, let us out! We are the saviors of Europe!” may eventually be heard by those who believe that a strong Germany would be the best sentinel of western civilization.

But Military Government officials genuinely concerned with building a new, better Germany believe that the men responsible for the Nazi scourge should be kept under quarantine for a long time to come. While advocating swift vexoneration of Followers and little sinners, these observers know that the leaders would wish to lead again and that the German people are only too willing to be led. As one importantly placed American official in Munich put it, “Behind the fence of Moosburg and some other camps in our zone, we’ve got the brains of Germany. Frankly, I don’t care whether these men still call themselves Nazis or not; I’m not worried about a revival of Nazism as such in Germany today. The real danger is that the same old forces which made Nazism possible will start a new nationalistic drive, ending in another catastrophe for Germany and for the world. The tide has already begun to run that way. Open the gate at Moosburg and let these men go home-two years from now, you’ll have another Putsch! The leaders of a new, democratic Germany must come out of the postwar melting pot. Otherwise, our victory was for nothing”.

THE END