In Sims “Celdagboek 2” bevinden zich achteraan ook twee pagina’s getiteld: “Middle Age and the Lady” door Abigail Powers uit ‘Munsay’s Magazine”, 1889. Het zijn richtlijnen voor vrouwen ‘op middelbare leeftijd”. Merkwaardig dat deze tijdschriften (bijna 60 jaar oud) toen beschikbaar waren, en dat Sims aandacht hierdoor werd getrokken. Reisden de tijdschriften mee in het kielzog van de bevrijders?

Het zijn oefeningen van Sim tijdens haar studie van het Engels.

Een voorpagina van het tijdschrift uit 1898:

“Munsey’s Magazine” verscheen vanaf 1889. Na wat opzoekwerk online vond ik de tekst in een ander tijdschrift van maart 1900: “The Puritan”, een tijdschrift van dezelfde uitgever (Frank A. Munsey Company).

Het artikel wordt daar toegeschreven aan Anne O’Hagan. Daar was de bewuste passage gemarkeerd:

De beginzin is lichtjes afwijkend van wat Sim schrijft: “These are a set of signs by which the most unobserving woman might know when middle age had made overtures to her“:

“Once”, continued the wise woman, “I drew up a set of signs by which the most unobserving woman might know when middle age had made overtures to her. Some of them I have already told you. These are they:

When tomorrow’s indigestion is more to her than today’s feast.

When she wonders patiently when he is going.

When between the acts is not so interesting to her as the acts themselves.

When she has no violent antipathy to her relatives.

When she begins to regard clothes as covering and not as lures.

When she adds no ‘except’ to her ‘not at home this evening.’

When she does not have to feign’ boredom, but to pretend enthusiasm.

When her griefs are not poignant unless they happen to be real.

When she thinks with a smile of the man who once wounded her vanity or broke her heart.

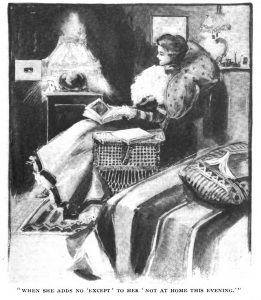

De tekening bij “When she adds no ‘except’ to her ‘not at home this evening'”:

Sim schrijft als auteur: “Abigail Powers”, zij schreef ook voor The Puritan, maar nergens wordt zij vermeld als auteur voor dit artikel.

Bovenaan de pagina (links) deze woorden:

“Ne frappe pas au coeur, tu n’y trouveras rien”.

Het komt uit “Les Châtiments, Le bord de la mer” (1853) van Victor Hugo.

Daaronder vertalingen van enkele Engelse woorden.

MIDDLE AGE AND THE LADY.

by Anne O’Hagan (“The Puritan”, March 1900)

Not by fading cheek and dimming eye does woman first realize the advance of middle age, but by the prudent inclination to take thought for tomorrow.

Some hold the tradition that the first white hair which she finds frosting her locks is the signal at which the woman with properly trained emotions apostrophizes her fleeting youth in such verse as she can recall and begins the struggle against her deadliest foe, middle age. The same tradition holds that the second white hair sends her scurrying either to hair dye or to the married ranks, where age is honorable, and that crow’s feet end in her all aspirations toward young frivolities.

That tradition is wrong scarcely needs the saying in these days, when it is never quoted except to be proved false. Half the women who have lived through them will tell you how blithely the occasional gray hairs may be borne; how it is never they that suggest the end of youth; how their coming is unheeded, and how their absence does not prolong the cheerful summer time.

“The conviction of middle age, compared with which the conviction of sin is a slight thing,” says November, who has weathered early autumn and come out serenely into Indian summer, “has nothing to do with externals. Your mirror may show you a patch of white upon your temple, and a network of fancy stitches under your eyes, and you will never think of connecting these with the crime of growing old. It is no more to you than the evidences of his guilt shown at his trial would be to a perfectly innocent man. You know that you are young! You never question your divine possession; your friends may make demands upon you for christening mugs and rattles, and you may be godmother half a score of times, and it is no more to you than being bridesmaid. You and age are not acquainted. But there comes a day! And then it isn’t your mirror which shows you that you are aging, and it isn’t your best friend’s array at the kindergarten or the primary school that makes you ask yourself whither you are going. It is something quite different!”

She paused; and those to whom middle age had not yet signaled and those who were pretending to be also uncalled, leaned forward breathlessly. November inclined toward them earnestly.

“It is this,” she said solemnly. “You suddenly realize that tomorrow’s indigestion means more to you than tonight’s feast. And when you reach that state, my dear girls, in the mental, moral, or physical world, you are in the clutches of middle age. You will struggle, but the struggle will be vain, as the funeral verses put it. You are already delivered over to the enemy when you choose tomorrow’s, comfort rather than to night’s pleasure; when you even deliberate between the two.”

She leaned back and looked at her hearers. The girl who had rejected tea on the ground of nerves hastily poured herself out a cup, but November smiled. Not by such transparent devices is the insidious enemy put to flight.

There were among November’s hearers some of whom their foes said that they were remarkably well preserved. These fell into a reflective state upon listening to the words from the wise woman. Was it indeed true that not upon the check or brow was the withering touch of age first laid, but upon the spirit?

Was it true that instead of spending hours at the masseuse’s, they should have been upon their knees entreating Providence for a fresh heart? And thus reflecting, they recalled many things.

This one saw herself, no less roseate and golden than ever before, seated in just that part of the opera house she liked the best. She held a program in her hand, and when its sixth number had been played, she cast her eyes over it. There was the thing she loved of all music the most: the strains that meant “infinite passion and the pain of finite hearts that yearn.”

She never heard the intermezzo from “Cavalleria” without the momentary constriction of heart and throat, the suffusion of eyes and the tense breathlessness, that spell emotional happiness for the young. That night she said crossly: “Now, why couldn’t they have put the intermezzo farther up? It’s the tenth number, and what with this atrocious encoring, it will be midnight before we get to it.”

“Don’t you want to stay?” someone had asked her. And she had hesitated and replied:

“No. No, I don’t think I do. It gives me such a headache to lose my sleep.”

And had those words rung the curtain down on youth for her? She frowned and sighed and made a silent vow that another time she would take the headache-ignoring quite that when one reaches the place where she de liberates which road to choose, she is already middle aged, and that the choice does not matter.

“I, myself,” said November, becoming reminiscent, “was well along into the enemy’s country before I realized my state. There had been a time when the first boon I begged of destiny was plenty of callers —- admirers —- danglers —whatever you call ‘em. Men, I mean. Then suddenly I awoke to the fact that I had preferences. I wanted the men to be interesting. A train tagging at my heels was no longer enough. I would rather have a smaller roll call and a more amusing one. That is a very bad sign. When you begin to discriminate among those who are succinctly known to the intelligence offices as ‘followers’, youth is making ready to sing her swan song. But I didn’t know this then. And I discriminated.”

She sighed and paused and then began again.

“Discrimination thinned the ranks considerably,” she announced, “and for a time I rejoiced in the change. Those who remained were so interesting — for a fortnight or a sixmonth or whatever it was! Then I began to reason that a choice coterie of interesting danglers was not what I craved, but one exciting dangler! And then, if I had only known it, youth was making her most formal farewells.

“I lost the coterie; it’s so easy to accomplish a thing like that! And I kept the exciting dangler. Even that is not difficult. And one evening when I knew the exciter was coming: to say pleasantly exciting and entirely meaningless things to me, I found that I did not feel like dressing for my part. The preservation of my lilac organdie and my buckled slippers seemed to me of greater moment than the impression I was to make upon my dangler.

I donned them, through force of habit, but with inward rebellion. And when a woman weighs the impression she is to create upon any man against her bill at the French laundry or the shoe store, youth is fleeing fast.

“The exciting dangler came and did not excite. It was no fault of his, poor man; he was what he had always been. But in the pauses-pauses in a tête-à tête, by the way, mean either middle age or -— the other thing. I found myself saying to myself: ‘I wonder when he means to go. And that meant for me that youth’s skirts were just disappearing around the corner in a flutter, and that I might never hope to clutch them again.”

“Do you think it is a bad sign,” anxiously inquired someone, “if one really means it when she leaves word that she is at home to no one?”

“It is one of the most unmistakable symptoms,” declared November vigorously. “To announce to your butler or your maid that you will not see anyone that evening, and not follow the order with an elaborately careless and indifferent ‘unless’, means that you are bound, hand and foot, to the hideous triumphal chariot of the all victorious fiend. Why, do you not see what it means? Youth, real youth, just out, gowns herself in her prettiest frock, arranges the flowers and the lights, and with flushed face and beating heart waits for any card to be handed in. All things and all people are untried. There may be mines of amusement in almost any one. Any ring at the door bell may be his royal highness, the Prince Charming. Think, then, what a long road one has traveled from this state of blissful, ignorant expectation, when one is able to say ‘at home to no one,’ and is content to be at home to no one.

“Once”, continued the wise woman, “I drew up a set of signs by which the most unobserving woman might know when middle age had made overtures to her. Some of them I have already told you. These are they:

“When tomorrow’s indigestion is more to her than today’s feast.

“When she wonders patiently when he is going.

“When between the acts is not so interesting to her as the acts themselves.

“When she has no violent antipathy to her relatives.

“When she begins to regard clothes as covering and not as lures.

“When she adds no ‘except’ to her ‘not at home this evening.’

“When she does not have to feign boredom, but to pretend enthusiasm.

“When her griefs are not poignant unless they happen to be real.

“When she thinks with a smile of the man who once wounded her vanity or

broke her heart.”

November, wise with the expensive wisdom of experience, told the truth, but not the whole truth. Middle age, the detested benefactor of woman, makes itself known in these ways far more than by the silver hair and hollow cheek of which the sentimentalist has spoken for some centuries back. But November, telling the signs by which middle age may be unmistakably known, did not tell the struggles by which these signs are met.

Any Sunday paper will inform you that the matron of advancing age or the spinster of vanishing youth ceaselessly brushes her locks, scrubs and rubs her face, anoints her neck, and makes a good fight against the outward and visible signs of a hated state. But no Sunday paper yet has told of the struggle against the state itself.

Jacintha, informed that the foe is upon her, by her inclination to yawn at the airiest persiflage between the third and the fourth acts, fights against the inclination, stubbornly, valiantly, pitifully. Not only does she smother the yawn as good manners demand, but she declares to the inclination that it, too, shall be subdued. She flashes her eyes; she smiles more conspicuously; she laughs. She bids the yawn retire before the torrent of her airy eloquence. She waves her fan vigorously; she uses her opera glasses with almost hysterical energy. People remark that it is curious about Jacintha; that she seems to be growing silly as she grows older. And they never guess that Jacintha is spreading a lure for youth.

When Jacintha, no longer feeling any very tempestuous emotion at the sight of a sunset, and realizing the awful meaning of her indifference, fairly lashes her emotions into activity, people say again that she grows sillier every day.

When, finding that she prefers a peignoir and a couch and a book to a sleigh ride or a dance, and fearing to yield to her preference, she attends every festivity to which she is invited, people wonder how her mother’s daughter can be such a gadabout.

She is like one who knows that she has involuntarily swallowed a poison, and who makes constant fight against its languorous influence, trotting wildly up and down without seeming aim or purpose. But no laudanum was ever yet distilled so subtly strong as this narcotic against which Jacintha and her sisters struggle.

“Why do they struggle?”

The wise November in the placid Indian summer asked the question.

“They don’t know what they struggle against,” she said, “what comfort, what peace of mind, what good humor, what toleration, what ease of body and soul. These poet people have many sins for which to answer, but none worse than this, that they have made all other states than youth and love which are, as a matter of fact, two highly uncomfortable ones — seem unattractive. Youth is pretty enough for poems, and love is a fine thing -— in tragedies. But why any woman should make desperate struggles for them when she will be a thousand times as comfortable by letting them go, is a mystery to me — now that I’ve ceased to struggle. Think how happy the laudanum swallower would be to sit down and doze! That happiness is nothing compared to a woman’s the day she decides to give up the tight for the discomforts of adolescence, and to be frankly middle aged. The profession of perpetual youth is too wearing for the average constitution.”